Building a Document Extraction Engine: A Field Guide

Every interesting document system starts with the same problem: you have unstructured documents and you need structured data. The documents contain information, but it’s trapped in paragraphs and clauses and headers. You can’t query it, filter it, or connect it to other data until you extract it into something usable.

This is the implementation story of building a document extraction engine. Not extraction for a single purpose, but a general-purpose engine that feeds multiple downstream uses: relational databases for structured queries, vector databases for semantic search, and potentially graph databases for relationship traversal. The same extraction pipeline serves all of them.

I’ve built variations of this a few times. What follows is what actually works, what doesn’t, and where the complexity hides.

What We’re Extracting

Before talking about how, let’s be clear about what.

Document metadata is the basic “what is this document” information:

- Title (extracted from content, because filenames lie)

- Document type (contract, invoice, memo, correspondence, service document, etc.)

- Document date

- Source system and location

Entities are the “who” of the document:

- People mentioned

- Organizations

- Agencies

- Courts (for legal documents)

- Any other named actors

Identifiers are reference data that needs exact matching:

- Addresses

- Email addresses

- Phone numbers

- Account numbers

- Case numbers

- Contract identifiers

Descriptive metadata is what the document is about:

- Topics and themes

- Key dates referenced (not the document date, but dates mentioned in content)

- Industry or domain indicators

- Other contextual keywords

These four categories matter because they have different storage needs, different search behavior, and different extraction characteristics. More on that later.

The Document Type Problem

Document type classification seems simple. It isn’t.

We give the extraction model a list of allowed document types: contract, invoice, service agreement, memo, correspondence, report, and so on. The user can configure this list for their domain. The model classifies each document into one of these types.

The first lesson: the list needs to be right-sized. Too few types and the classification isn’t useful. If everything is either “document” or “other,” you haven’t learned anything. Too many types and classification becomes inconsistent. The model (and humans) will disagree about whether something is a “service agreement” or a “master services agreement” or a “consulting agreement.”

We landed on letting users define their own type hierarchy, but providing guidance: aim for 8 to 15 top-level types, with optional subtypes if needed. And always include an “other” or “unclassified” type for documents that genuinely don’t fit. Forcing everything into predefined buckets creates garbage classifications.

The second lesson: document type classification should happen early and separately. We run it as its own extraction call before other extraction. Why? Because document type informs how we extract everything else. The entities we expect in a contract differ from the entities we expect in correspondence. The identifiers in an invoice differ from the identifiers in a legal brief. Knowing the document type first lets us tune subsequent extraction.

The third lesson: when someone adds a new document type, you have a decision to make. Do you re-classify existing documents? Our answer was no, not automatically. New types apply going forward. If a user wants to retroactively classify, they can trigger that explicitly, but we don’t assume they want to re-process thousands of documents just because they added a type.

The Extraction Schema Evolution

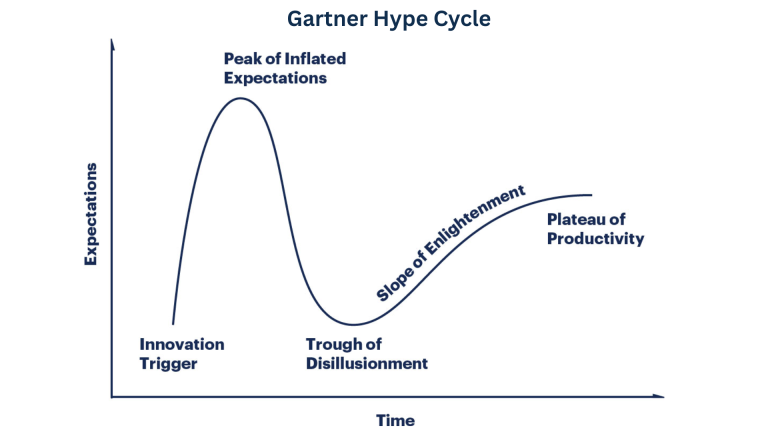

This is where most of our iteration happened. Getting the extraction schema right took five distinct phases, and each one taught us something we couldn’t have learned upfront.

Phase 1: The Fixed Field List

We started with a predetermined list of fields to extract. For every document, extract: title, document type, people mentioned, organizations mentioned, key dates, and a handful of other specific fields.

Clear instructions. Predictable output structure. Easy to validate.

It worked, mostly. But we kept finding documents where something obviously important wasn’t captured. A contract with unusual indemnification language, but nothing in the extracted data indicated that. A memo about a specific regulatory issue, but the regulation wasn’t captured because “regulation name” wasn’t in our field list.

Phase 2: The Flexible Field List

So we opened it up. Instead of “extract exactly these fields,” we said “here are the types of fields we want, but capture other important information you find.”

This was worse.

The model extracted everything. Page numbers. Formatting notes. The name of every person mentioned in passing. Marginally relevant dates. We got more data, but most of it was noise. The signal-to-noise ratio dropped so far that the extracted data became harder to use, not easier.

Phase 3: The Exclusion List

We tried adding boundaries. We called these “extraction boundaries,” though we experimented with other names.

This was a list of what not to extract:

- Procedural or administrative details (filing dates unrelated to content, page numbers, formatting)

- Routine participants (notaries, clerks, administrative staff unless they’re actually relevant)

- Generic terms that appear everywhere and add no information

- Information already present in source system metadata

This helped. We got back to extracting meaningful information without drowning in noise. But we still had a structural problem.

Phase 4: Categorizing Extracted Data

We realized we were treating all extracted data the same, but entities, identifiers, and descriptive metadata have fundamentally different characteristics.

Entities need normalization and linking. “John Smith,” “J. Smith,” and “Mr. Smith” might all be the same person. Organizations appear under different names, abbreviations, and legal entities. Entity extraction needs to feed into an entity resolution process that links mentions across documents.

Identifiers need exact matching. An account number is an account number. You either want documents with account “12345” or you don’t. Identifiers don’t benefit from fuzzy matching or semantic similarity. They need precise lookup.

Descriptive metadata needs semantic understanding. Topics and themes benefit from normalization (so “M&A” and “mergers and acquisitions” are treated as related) but also need to support semantic search. “Documents about corporate restructuring” should find documents even if they don’t use that exact phrase.

Once we separated these categories, we could store and process them appropriately. Entities go into normalized tables with relationship tracking. Identifiers go into lookup tables optimized for exact match. Descriptive metadata goes into both relational storage (for filtering) and vector storage (for semantic search).

Phase 5: Scoped Extraction Calls

The last lesson was about extraction scope within a single document.

When we asked the model to extract everything in one call, it missed things. Not always, not predictably, but often enough to matter. Ask for entities, identifiers, topics, dates, and document characteristics all at once, and some of them get dropped.

The fix was multiple focused extraction calls:

- One call for document classification and basic metadata

- One call for entity extraction

- One call for identifier extraction

- One call for topic and descriptive metadata

Each call has a narrower scope and clearer instructions. The combined results are more complete than single-call extraction.

Yes, this means more API calls and higher cost. It’s worth it. The point of extraction is to make documents findable and usable. Missing important data defeats the purpose.

We run these calls in parallel where possible. Document classification has to happen first (because it informs other extraction), but entity extraction and identifier extraction can run simultaneously. This keeps latency reasonable despite multiple calls.

Handling Long Documents

Every LLM has a context limit. Documents often exceed it.

A 50-page contract doesn’t fit in a single extraction call. Neither does a 200-page report or a large set of correspondence compiled into one file. You need a strategy.

Our approach: chunk the document, extract from each chunk, merge results.

But chunking for extraction isn’t the same as chunking for retrieval. For retrieval, you want semantically coherent chunks that stand alone. For extraction, you want chunks that preserve enough context to identify entities and relationships correctly.

We use a proprietary chunking algorithm that does several things:

- Respects document structure (section boundaries, paragraph breaks)

- Adds document-level context to each chunk (document title, type, and section path)

- Maintains overlap so entities that span chunk boundaries aren’t missed

- Tracks chunk position so we can deduplicate extracted data that appears in overlapping regions

The merge step is important. The same entity might be extracted from multiple chunks. The same identifier might appear several times. We deduplicate and consolidate, keeping track of where in the document each piece of information appeared.

One thing we learned: entity extraction handles chunking better than you’d expect. Names are usually self-contained. But relationship extraction (who is related to whom, what organization does a person belong to) suffers when the relevant information spans chunks. We don’t try to extract complex relationships from chunked documents. We extract entities and let downstream processes infer relationships.

Where the Extracted Data Goes

The extraction engine feeds multiple storage systems, each serving different query patterns.

Relational database stores structured extracted data: document metadata, normalized entities, identifiers. This supports SQL queries like “show me all contracts mentioning Organization X signed after 2023” or “find documents where Person Y is listed as a party.”

Vector database stores embedded chunks for semantic search. But here’s the key: we don’t just embed the raw text. Each chunk’s vector payload includes document metadata, extracted entities, and identifiers found in that chunk. This enables hybrid search. You can do semantic similarity (“find documents about supply chain disruption”) filtered by structured criteria (“but only contracts with Acme Corp”).

Graph database is a natural extension we’ve designed for but implement based on client needs. The extracted data already contains the nodes (entities) and edges (relationships like “Person X works for Organization Y” or “Contract A references Contract B”). Loading this into a graph database enables traversal queries: “show me all documents connected to this entity within two hops.”

The extraction pipeline doesn’t need to know which downstream systems will consume its output. It produces normalized, categorized extracted data. Storage and indexing decisions happen downstream.

The Title Extraction Problem

This sounds trivial. It isn’t.

Documents have titles, but filenames often don’t match. “Document1_final_v2_REVISED.docx” tells you nothing. The actual title is buried in the content, maybe in a header, maybe in the first paragraph, maybe in metadata that may or may not be populated.

We extract title as part of the initial metadata pass. The model looks at:

- Document metadata fields (if present)

- Headers and title formatting

- First lines of content

- Letterhead or header blocks

The instruction is: “Extract the document’s actual title as a human would describe it, not the filename.”

This works well for documents with clear titles. For documents without obvious titles (like email chains or informal memos), the model generates a descriptive title based on content. “Email thread regarding Q3 budget review” is more useful than “RE: RE: RE: FW: budget.”

We flag generated titles differently from extracted titles. Downstream systems can choose whether to display them differently or allow user override.

Validation and Quality

Extraction quality varies by document. Clean, well-structured documents extract reliably. Messy documents, scanned PDFs, documents with unusual formatting, all produce lower-quality extraction.

We handle this several ways.

Confidence scoring: The extraction model provides confidence indicators. Low confidence extractions get flagged for human review rather than treated as authoritative.

Sampling-based validation: We regularly sample extracted data and compare against human review. This catches systematic errors (the model consistently misclassifying a document type, or missing a common entity pattern) that wouldn’t surface from individual document review.

Feedback integration: When users correct extracted data, those corrections inform future extraction. Not through model fine-tuning (which is expensive and slow) but through improved prompts and examples.

Source quality tracking: Some source systems produce consistently clean documents. Others produce garbage. We track extraction quality by source, which helps prioritize where to focus improvement efforts.

What Broke and What We Changed

Entity normalization across documents was harder than expected. The same organization appears as “Acme Corp,” “Acme Corporation,” “ACME,” and “Acme Corp, Inc.” within a single client’s documents. Our initial approach (aggressive normalization) created false matches. Our current approach (conservative matching with human-in-the-loop verification for important entities) is safer but leaves some fragmentation.

Schema evolution created ongoing pain. When we added new extraction fields or changed how existing fields worked, old documents had different data structures than new ones. Re-extracting everything is expensive. We settled on “extract on access” (re-extract when a document is retrieved if its extraction version is outdated) plus batch re-extraction for high-value document sets.

Identifier extraction precision required iteration. Early versions extracted anything that looked like an identifier. Phone numbers in footer boilerplate. Email addresses in confidentiality notices. We added filtering for boilerplate locations and common false-positive patterns.

Multi-language documents still aren’t fully solved. The extraction works, but entity normalization across languages (the same organization named differently in English and Spanish documents) requires more sophisticated matching than we initially built.

Extending to New Use Cases

The extraction engine we’ve described is general purpose. It doesn’t know what you’ll do with the extracted data. That’s intentional.

When a new use case emerges, the questions are:

- Do we need to extract new fields? (Sometimes yes, often no.)

- Do we need new document types? (Add them to the configurable list.)

- Do we need different downstream storage or indexing? (That’s a separate system.)

The legal search system described elsewhere uses this extraction engine for document processing, then adds its own chunking-for-retrieval, access control, and search agent layers. A compliance monitoring system would use the same extraction, add its own alerting and tracking logic. A contract management system would use the same extraction, add its own obligation tracking and deadline management.

Keeping extraction general purpose means new use cases don’t require rebuilding the foundation.

A Final Word

The extraction engine is never “done.” Document types evolve. Extraction quality improves. New fields become relevant. Schema versions accumulate.

But getting the architecture right (categorized extraction, scoped calls, parallel processing, multi-destination storage) means improvements compound rather than requiring rewrites. That’s the goal: a foundation that gets better over time rather than one you replace every few years.